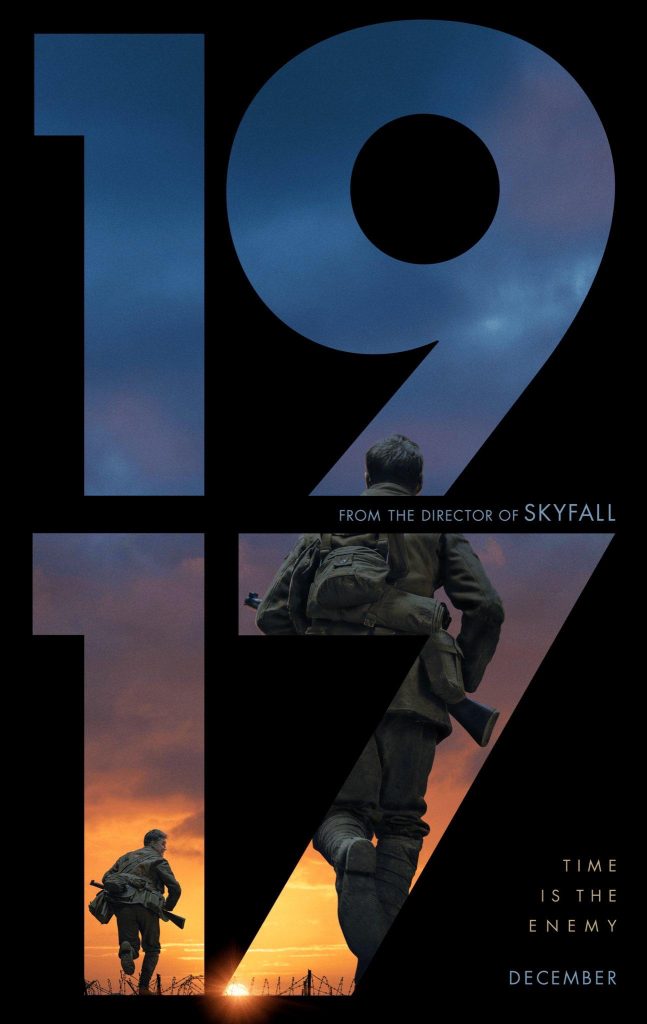

World War 1 films have been prolific over the years, but many of them did not generate in the United States and therefore were not seen in large numbers here. This is surely owing to the fact that our army was only involved during the war’s final year and therefore the stories from the American perspective are limited when compared to those of the Civil War, World War 2, or Vietnam. In England, France, and Germany, however, the Great War and its history is treated with reverence and the veterans were honored and respected throughout the duration of their lives. The recently released 1917 looked to be a visual feast and a tribute to the soul and character of the World War 1 British soldier.

1917

The plot is made mostly clear by the intriguing trailer, but I’ll flesh out some of the points without giving anything away. The Germans – or Bosches or Huns, in Great War parlance – have pulled back from a sector of the front lines in what appears to be a retreat. It is actually a feint, as the Germans have re-established a new and purportedly much stronger defensive position in another sector. This information is gleaned through aerial photographs provided to the 8th Battalion. Unfortunately the telephone lines have been cut, so there is no way to warn the 2nd Battalion that they are about to attack a heavily fortified enemy and likely be annihilated. General Erinmore (Colin Firth) is aware that a Lieutenant Blake in the soon-to-be-doomed second battalion has a little brother who is a Lance Corporal in the eighth battalion and he summons him with orders of an almost impossible mission: cross the nine miles to the second battallion’s new position on foot before dawn the next day and deliver official orders to call off their attack.

General Erinmore (Colin Firth) explaining the overly simple mission. If you’re a Marvel superhero, that is…

Lance Corporal Blake and fellow Lance Corporal Schofield, portrayed respectively by young British actors Dean-Charles Chapman and George Mackay, serve as our ground-level guides through the nightmarish hell of the Western Front. While most of the early hullaballoo surrounding 1917 concerned the editing that allowed the film to appear as if it were shot using just a few, uninterrupted takes*, the historical authenticity and set design are breathtaking to behold. After we first meet Blake and Schofield, they make their way down a winding series of trenchworks that seemingly go on forever and are packed on both sides with British soldiers who have been forced to adopt a lifestyle combining the traits of earthworms and sardines. This is how the men who served on the Western Front lived, for to raise one’s head above the dugout during daylight hours was an invitation to draw fire. This is beautifully captured and forces the viewers to ponder the depths of our respective imaginations. As Paul Fussell wrote in his classic book The Great War and Modern Memory, “The British trenches were wet, cold, smelly, and thoroughly squalid.” Ok, then.

Young British Lance Corporals Blake (Dean-Charles Chapman) and Schofield (George Mackay) navigate the deserted hell of No Man’s Land in “1917”

1917 is a visceral experience, but then so was the Great War. In addition to the claustrophobia of the trenches, we are treated to a nearly point-of-view experience of the infamous No Man’s Land, a broken wasteland featuring tangled rolls of barbed wire, squelching mud, crater holes filled with corpses in varying stages of putrefaction and bloated, and overfed vermin the size of house cats. Once free of No Man’s Land and the trenches, Blake and Schofield continue their odyssey while battling their fears and the ticking clock. What of the performances of Chapman and MacKay? In my opinion, they were both wonderful, delivering raw and heartachingly honest portrayals. The film is as much about friendship and devotion to one another as it is about patriotic duty and the horrors of the war.

There is much more to be said about 1917 but these are conversations to be had after the movie has been seen, and 1917 is more than worth the price of admission. Some films are called a visual feast, and for lack of a better description that is certainly true in this case. Hopefully you weren’t as foolish as The Doctor and decided to take in a Saturday matinee on opening weekend at 1:10, an hour too early for even yours truly to start drinking… at least, by any account that I will ever admit to.

* The film, obviously, was not shot in 3 or 4 unbroken takes. This would be impossible. But through a masterful editing sleight-of-hand, 1917 looks like it was shot that way. Praise should be heaped on renowned director Sam Mendes for his vision and to everyone else involved for carrying it out. As a British soldier might have said with sincerity “Well done, lads.”